Difference between revisions of "Commentators:R. Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin (Netziv)/0"

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

(Import script) |

m |

||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

<page type="Basic"> | <page type="Basic"> | ||

| − | + | <h1>R. Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin (Netziv)</h1> | |

| − | <h1>R. Naftali | + | <stub></stub> |

| − | <stub/> | ||

| − | |||

<div class="header"> | <div class="header"> | ||

<infobox class="Parshan"> | <infobox class="Parshan"> | ||

<title>Netziv</title> | <title>Netziv</title> | ||

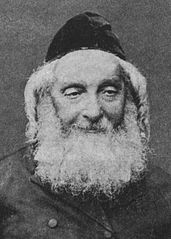

| − | + | <img style="max-width:50%;" src="/Media/Parshanim/Netziv/Picture.jpg" alt="Netziv" title="Netziv"/> | |

| − | + | <row> | |

| − | + | <label>Name</label> | |

| − | + | <content> | |

| − | + | <div dir="ltr"> | |

| − | + | R. Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin (Netziv) | |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | <div dir="rtl"> | |

| − | + | ר' נפתלי צבי יהודה ברלין (נצי"ב) | |

| − | + | </div> | |

| − | + | </content> | |

| − | + | </row> | |

| − | + | <row> | |

| − | + | <label>Dates</label> | |

| − | + | <content>1816 – 1893</content> | |

| − | + | </row> | |

| − | + | <row> | |

| − | + | <label>Location</label> | |

| − | + | <content>Russia / Poland</content> | |

| − | + | </row> | |

| − | + | <row> | |

| − | + | <label>Works</label> | |

| − | + | <content>Ha'amek Davar on Torah, Commentaries on Midreshei Halakhah and Sheiltot, Meromei Sadeh, Shut Meshiv Davar</content> | |

| − | + | </row> | |

| − | + | <row> | |

| − | + | <label>Exegetical Characteristics</label> | |

| − | + | </row> | |

| − | + | <row> | |

| − | + | <label>Influenced by</label> | |

| − | + | <content>Vilna Gaon</content> | |

| + | </row> | ||

| + | <row> | ||

| + | <label>Impacted on</label> | ||

| + | </row> | ||

| + | |||

</infobox> | </infobox> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

| − | |||

<category>Background<fn>This page incorporates information from the dissertation of G. Perl, "A Window into the Intellectual Universe of Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehudah Berlin," Harvard University, 2006 (hereafter: Perl, Berlin).</fn> | <category>Background<fn>This page incorporates information from the dissertation of G. Perl, "A Window into the Intellectual Universe of Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehudah Berlin," Harvard University, 2006 (hereafter: Perl, Berlin).</fn> | ||

| − | <p | + | <p><strong></strong></p> |

<subcategory>Life | <subcategory>Life | ||

| − | + | <ul> | |

| − | + | <li><b>Name</b> | |

| − | + | <ul> | |

| − | + | <li><b>Hebrew name</b> – ‏ר' נפתלי צבי יהודה ברלין (נצי"ב)‏</li> | |

| − | + | <li><b>Yiddish name</b> – R. Hirsch Leib</li> | |

| − | + | </ul> | |

| − | + | </li> | |

| − | + | <li><b>Dates</b> – 1816 – 1893</li> | |

| − | + | <li><b>Location</b> – Born in the Lithuanian town of Mir, lived his adult life in Volozhin.</li> | |

| − | + | <li><b>Education</b> – Little is known of the Netziv's early childhood. He entered Yeshivat Etz Chaim at Volozhin at the age of 14 ½.<fn>This was after having married the daughter of the Rosh Yeshivah, see below, Family. See, however, Perl, Berlin: xix, note 15, where he cites other reports claiming that the Netziv went to Volozhin three years earlier, prior to his marriage. See also ibid.: xx, where Perl argues convincingly against the claim in Mekor Baruch that the Netziv was a boy of "average intelligence".</fn></li> | |

| − | + | <li><b>Occupation</b> | |

| − | + | <ul> | |

| − | + | <li>By the age of 25, the Netziv had replaced his father-in-law in giving the daily shiur at the Volozhin Yeshivah.<fn>Already at this young age, the Netziv was known as "one of the most celebrated Talmudists in Russia". See M. Lilienthal, Max Lilienthal, American Rabbi: Life and Writings, ed. David Phlipson (New York, 1915), 344, and Perl, Berlin: xxi.</fn></li> | |

| − | + | <li>The Netziv became assistant Rosh Yeshivah at Volozhin in 1849, under his brother-in-law R. Eliezer Isaac Fried. When the latter died in 1853, the Netziv was appointed Rosh Yeshivah,<fn>In 1856, R. Yosef Baer Soloveitchik unsuccessfully disputed the appointment of the Netziv as Rosh Yeshivah.</fn> a position he held until the Yeshivah's closing in 1892.<fn>For a full discussion of the Yeshivah's closing, see J. Schacter, "Haskalah, Secular Studies and the Close of the Yeshiva in Volozhin in 1892," Torah u-Madda Journal 2 (1990, hereafter: Schacter: Close) 76-133. Schacter also has an important depiction of the political struggles within the Yeshivah in the years prior to its closing, including the animosity felt by some toward the Netziv's second wife, and the dispute over whether R. Chaim Berlin or R. Chaim Soloveitchik should succeed the Netziv as Rosh Yeshivah.</fn></li> | |

| − | <li><b> | + | <li>As Rosh Yeshivah of the preeminent Jewish educational institution of the era, the Netziv was also a prominent leader of Lithuanian Jewry.</li> |

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li><b>Time Period</b> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>During the Netziv's lifetime, Lithuania and Poland were controlled by Imperial Russia, with the Netziv's formative years lived under the oppressive legislation of Nicholas I (1825-1855), which sought to encourage the acculturation of the Jews.<fn>These efforts largely failed, and, despite the legislation, this period was marked by a flourishing of Jewish intellectual activity.</fn></li> | ||

| + | <li>Defining movements of 19th century Judaism had their beginnings, or saw significant development, during this period, including the Haskalah, Hasidism, the Musar movement, and Zionism.</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li><b>World outlook</b> – The Netziv had a nuanced attitude toward secular studies, the Haskalah, and its literature.<fn>See the discussion in Schacter, Close: 101-104. He himself was an open-minded and avid reader of the Haskalah press (even sometimes citing it in his Torah commentary – see below, Works, Printings), however he refused to officially allow secular studies in the Volozhin Yeshivah. In the contemporary Jewish press, the Netziv was both attacked by Maskilim for not introducing secular studies into the Yeshivah, and defended by Maskilim as being open-minded toward Haskalah and not an anti-Haskalah zealot like some of his contemporaries.</fn> He was active in the Chibbat Tziyyon movement.<fn>Within the Yeshivah, however, he refused to allow any active movements (even ones that he supported) that might distract students from their Torah studies. See Schacter, Close: 104 and note 120. Regarding the Netziv's dispute with Zionist leaders concerning enforcement of Torah observance in settlements in the land of Israel, see G. Perl, "'No Two Minds are Alike': Tolerance and Pluralism in the Work of Neziv", Torah U-Madda Journal 12: 77-78.</fn></li> | ||

| + | <li><b>Family</b> – The Netziv's father, Yaakov Berlin, was a textile merchant descended from a rabbinic family. His mother was Batya Mirel of the Eisenstadt family.<fn>He was a descendant of R. Meir of Eisentstadt, author of Panim Meirot. Members of this family served as communal rabbis of Mir in the first half of the 19th century.</fn> The Netziv's first wife was Rayne Batya,<fn>She was the daughter of R. Yitzchak of Volozhin, the Rosh Yeshivah of Yeshivat Etz Chaim and son of R. Chaim of Volozhin. The Netziv was fourteen and a half when they were married. Rayne Batya died in 1871.</fn> and his second wife was his niece Batya Miryam.<fn>She was the daughter of the Netziv's sister and R. Yechiel Michel Epstein, and sister of R. Baruch Epstein.</fn> R. Chaim Berlin<fn>He was born when the Netziv was a mere sixteen years old.</fn> was his son from his first marriage, and R. Meir Bar-Ilan<fn>He was born in 1880, 48 years after his half-brother Chaim.</fn> was his son from his second marriage.<fn>The Netziv and Batya Miryam also had another son, Yaakov.</fn> The Netziv had several siblings, many of whom were part of the Torah world.<fn>These included Avraham Meir who was involved in the publication of the works of the Vilna Gaon, R. Eliezer Lipman who authored novellae on the Talmud, R. Netanel who was the Rabbi of a small town, Chaim who was a lay leader of the Vilna community and an active member of Chovevei Tzion, Lipshah who married Chaim Leib Shachor, from a wealthy and prominent rabbinic family, Rivkah (Meir Bar-Ilan reports that she married a man named Haslovitz, but other family members relate that she was baptized and married a Russian general. See Perl, Berlin: xix, note 14), and Michlah who married R. Yechiel Michel Epstein, the author of the Arukh Hashulchan.</fn> R. Baruch Epstein<fn>He was the author of the Torah Temimah commentary and Mekor Barukh (his autobiography which contains much material about the Netziv).</fn> was the Netziv's nephew, and R. Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk married the Netziv's granddaughter.</li> | ||

| + | <li><b>Teachers</b> – </li> | ||

| + | <li><b>Contemporaries</b> – R. Yitchak Elchanan Spektor, R. Yosef Baer Soloveitchik</li> | ||

| + | <li><b>Students</b> – The Netziv influenced thousands of students at the Volozhin yeshivah, including many of the religious and intellectual leaders of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </subcategory> | ||

| + | <subcategory>Works | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li><b>Biblical commentaries</b> | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

| − | <li></li> | + | <li>Ha'amek Davar<fn>1879-1880 (see below, Printings). G. Perl (Berlin: 284-287) presents convincing evidence that Ha'amek Davar was composed mainly in the 1860s and 1870s. For an analysis of the relationship between the Netziv's early work on Midrash (especially Eimek HaNetziv) and Ha'amek Davar, see ibid.: 287-317.</fn> – The major portion of a Torah commentary based largely on material originally presented in the Netziv's daily Parashat HaShavua shiur in the Volozhin Yeshivah. A separate section of the commentary, entitled Harchev Davar, presents more extensive discussions.</li> |

| + | <li>Rinah Shel Torah<fn>First published in 1886, and republished as the sixth volume of recent editions of Ha'amek Davar (see above).</fn> – A two part work consisting of a commentary on Shir Hashirim (Metiv Shir) and an essay on the roots of anti-Semitism (Shear Yisrael).<fn>An English translation of Shear Yisrael was published in H. Joseph, Why Anti-Semitism: A Translation of "The Remnant of Israel" (Northvale, NJ, 1996).</fn></li> | ||

| + | <li>Devar HaEimek<fn>Published in Jerusalem, 1988.</fn> – A collection of excerpts from the Netziv's writings related to verses in Neviim and Ketuvim.</li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| − | + | <li><b>Rabbinics</b> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <li><b>Rabbinics</b> | ||

<ul> | <ul> | ||

| − | <li><b>Talmudic novellae</b> – </li> | + | <li><b>Talmudic novellae</b> – Meromei Sadeh<fn>First published in Jerusalem, 1953-1959.</fn></li> |

| − | <li><b> | + | <li><b>Commentaries</b> |

| − | + | <ul> | |

| − | <li><b>Responsa</b> | + | <li>Ha'amek She'elah<fn>Vilna, 1861-67; and republished with additions in Jerusalem (multiple printings) by Mosad HaRav Kook.</fn> – Expansive commentary on the Geonic work Sheiltot DeRav Achai Gaon.<fn>The work includes an extensive introduction discussing the nature and history of Torah study, entitled Kidmat HaEimek (and given the name Darkah Shel Torah by the Netziv's son, R. Chaim Berlin). This introduction was published in an English translation by Rabbi E. Greenman as, "The Path of Torah" (2007). This work is emblematic of the Netziv's proclivity to focus on relatively obscure halakhic works, and its content typifies, among other things, his general interest in textual inaccuracies and anomalies within halakhic texts.</fn></li> |

| + | <li>Eimek HaNetziv<fn>First published in Jerusalem, 1959-1961.</fn> – Commentary on the Halakhic Midrash Sifre.<fn>According to Perl, Berlin: 40-63, this work represents the Netziv's earliest intellectual product, mostly composed in the 1830s and 1840s.</fn></li> | ||

| + | <li>Birkat HaNetziv<fn>First published in Jerusalem, 1970.</fn> – Commentary on the Mekhilta</li> | ||

| + | <li>Notes on Torat Kohanim<fn>Most recently published together with Birkat HaNetziv, Jerusalem, 1997.</fn></li> | ||

| + | <li>Imrei Shefer<fn>Warsaw, 1889, and republished in numerous editions.</fn> – Commentary on the Haggadah shel Pesach</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li><b>Responsa and letters</b> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>Meishiv Davar<fn>Responsa collected for publication at the end of the Netziv's life and published posthumously. It was republished with additions in Jerusalem, 1993.</fn></li> | ||

| + | <li>Iggerot HaNetziv<fn>Jerusalem, (2003). A collection of previously unpublished letters (as well as republished approbations).</fn></li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</li> | </li> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</subcategory> | </subcategory> | ||

| − | |||

</category> | </category> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<category>Torah Commentary | <category>Torah Commentary | ||

<subcategory>Characteristics | <subcategory>Characteristics | ||

| − | + | <ul> | |

| − | <li><b>Verse by verse / Topical</b> – </li> | + | <li><b>Verse by verse / Topical</b> – </li> |

| − | <li><b>Genre</b> – </li> | + | <li><b>Genre</b> – </li> |

| − | <li><b>Structure</b> – </li> | + | <li><b>Structure</b> – </li> |

| − | <li><b>Language</b> – </li> | + | <li><b>Language</b> – </li> |

| + | <li><b>Peshat and derash</b> | ||

| + | <ul> | ||

| + | <li>The commentary exhibits the Netziv's extensive knowledge of Hebrew grammar and syntax, and displays the Netziv's commitment to the method and content of Midrash Halakhah<fn>See Perl, Berlin: xxvi.</fn> and to the teachings of the Oral Law in general.<fn>The Netziv's typical exegetical approach is succinctly described by Temima Davidovitz ("קווים מאפיינים בפרשנותו של הנצי"ב מוולוז'ין", Iggud: Selected Essays in Jewish Studies Vol. 1: The Bible and Its World, Rabbinic Literature and Jewish Law, and Jewish Thought (2005): 86): "פתיחת הדיון בשאלות לשוניות לסוגיהן: מורפולוגיות, תחביריות, סמנטיות ומילונאיות, ולאחריה קישור הכתוב עם הנאמר במדרשי חז"ל, בהלכה ובאגדה כאחד, לצורך הפקת לקח דידקטי-אידאי מן הכתובים."</fn></li> | ||

| + | <li>The commentary is significantly influenced by the Netziv's Lithuanian Mitnagdic focus on the religious significance of Torah study.</li> | ||

| + | <li>In his introduction to the commentary, Kidmat HaEimek,<fn>Not to be confused with his identically titled introduction to Ha'amek She'elah.</fn> The Netziv sets forth a view of <i>peshuto shel mikra</i> based on the understanding that the Torah is generally meant to be interpreted more as poetry than as prose. Since poetry clearly intends for the reader to employ a subtle, less obvious kind of interpretation, readings that otherwise might be viewed as <i>derash</i> can actually be considered <i>peshat</i>.</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</subcategory> | </subcategory> | ||

| − | |||

<subcategory>Methods | <subcategory>Methods | ||

| − | + | <ul> | |

| − | <li> – </li> | + | <li> – </li> |

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</subcategory> | </subcategory> | ||

| − | |||

<subcategory>Themes | <subcategory>Themes | ||

| − | + | <ul> | |

| − | <li> – </li> | + | <li> – </li> |

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</subcategory> | </subcategory> | ||

| − | |||

<subcategory>Textual Issues | <subcategory>Textual Issues | ||

| − | + | <ul> | |

| − | <li><b> | + | <li><b>Printings</b> |

| − | + | <ul> | |

| − | <li><b>Textual layers</b> – </li> | + | <li>Ha'amek Davar was initially brought to press by the Netziv himself, and published in 1879-80. From that point until the end of his life, the Netziv recorded additional commentaries and notes (mostly written in the margins of his personal copy of Ha'amek Davar).</li> |

| + | <li>In 1938, a second edition was published by R. Meir Berlin (Bar Ilan), which included some 1500 additions.<fn>Appended at the end of each volume. These additions have been collated in one volume available <a href="http://hebrewbooks.org/31901">here</a>.</fn></li> | ||

| + | <li>In 1999, a new edition of Ha'amek Davar was published that incorporated the additions into the body of the commentary, and included further comments not included in the 1938 edition, taken from a manuscript the Netziv had written near the end of his life in preparation for republishing the work.<fn>See S. Gershuni, ‏"על כתיבת 'העמק דבר' ועל פירוש 'חסידיך'"‏, HaMa'ayan Tammuz 5772 (2012) that the publishers of the 1999 edition seem to have taken great liberties in editing these additions. Gershuni cites the Netziv's addition to Bereshit 15:18, where the Netziv references archaeological information from an article in the newspaper HaTzefirah, authored by future Zionist leader Nachum Sokolow. The addition appears in the 1938 edition, but was entirely left out of the 1999 edition with no explanation. Gershuni suspects that the editors were uncomfortable with the content of this addition.</fn></li> | ||

| + | <li>From 2006-2011, a new annotated edition was produced by R. Mordechai Copperman.</li> | ||

| + | </ul> | ||

| + | </li> | ||

| + | <li><b>Textual layers</b> – </li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</subcategory> | </subcategory> | ||

| − | |||

</category> | </category> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<category>Sources | <category>Sources | ||

<subcategory>Significant Influences | <subcategory>Significant Influences | ||

| − | + | <ul> | |

| − | <li><b>Earlier Sources</b> – </li> | + | <li><b>Earlier Sources</b> – </li> |

| − | <li><b>Teachers</b> – </li> | + | <li><b>Teachers</b> – </li> |

| − | <li><b>Foils</b> – </li> | + | <li><b>Foils</b> – </li> |

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</subcategory> | </subcategory> | ||

| − | |||

<subcategory>Occasional Usage | <subcategory>Occasional Usage | ||

| − | + | <ul> | |

<li></li> | <li></li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</subcategory> | </subcategory> | ||

| − | |||

<subcategory>Possible Relationship | <subcategory>Possible Relationship | ||

| − | + | <ul> | |

<li></li> | <li></li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</subcategory> | </subcategory> | ||

</category> | </category> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

<category>Impact | <category>Impact | ||

<subcategory>Later exegetes | <subcategory>Later exegetes | ||

| − | + | <ul> | |

<li></li> | <li></li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</subcategory> | </subcategory> | ||

| − | |||

<subcategory>Supercommentaries | <subcategory>Supercommentaries | ||

| − | + | <ul> | |

<li></li> | <li></li> | ||

</ul> | </ul> | ||

</subcategory> | </subcategory> | ||

| − | |||

</category> | </category> | ||

| − | |||

</page> | </page> | ||

</aht-xml> | </aht-xml> | ||

Latest revision as of 01:13, 27 July 2015

R. Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin (Netziv)

This page is a stub.

Please contact us if you would like to assist in its development.

Please contact us if you would like to assist in its development.

| |

| Name | R. Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin (Netziv) ר' נפתלי צבי יהודה ברלין (נצי"ב) |

|---|---|

| Dates | 1816 – 1893 |

| Location | Russia / Poland |

| Works | Ha'amek Davar on Torah, Commentaries on Midreshei Halakhah and Sheiltot, Meromei Sadeh, Shut Meshiv Davar |

| Exegetical Characteristics | |

| Influenced by | Vilna Gaon |

| Impacted on | |

Background1

Life

- Name

- Hebrew name – ר' נפתלי צבי יהודה ברלין (נצי"ב)

- Yiddish name – R. Hirsch Leib

- Dates – 1816 – 1893

- Location – Born in the Lithuanian town of Mir, lived his adult life in Volozhin.

- Education – Little is known of the Netziv's early childhood. He entered Yeshivat Etz Chaim at Volozhin at the age of 14 ½.2

- Occupation

- By the age of 25, the Netziv had replaced his father-in-law in giving the daily shiur at the Volozhin Yeshivah.3

- The Netziv became assistant Rosh Yeshivah at Volozhin in 1849, under his brother-in-law R. Eliezer Isaac Fried. When the latter died in 1853, the Netziv was appointed Rosh Yeshivah,4 a position he held until the Yeshivah's closing in 1892.5

- As Rosh Yeshivah of the preeminent Jewish educational institution of the era, the Netziv was also a prominent leader of Lithuanian Jewry.

- Time Period

- During the Netziv's lifetime, Lithuania and Poland were controlled by Imperial Russia, with the Netziv's formative years lived under the oppressive legislation of Nicholas I (1825-1855), which sought to encourage the acculturation of the Jews.6

- Defining movements of 19th century Judaism had their beginnings, or saw significant development, during this period, including the Haskalah, Hasidism, the Musar movement, and Zionism.

- World outlook – The Netziv had a nuanced attitude toward secular studies, the Haskalah, and its literature.7 He was active in the Chibbat Tziyyon movement.8

- Family – The Netziv's father, Yaakov Berlin, was a textile merchant descended from a rabbinic family. His mother was Batya Mirel of the Eisenstadt family.9 The Netziv's first wife was Rayne Batya,10 and his second wife was his niece Batya Miryam.11 R. Chaim Berlin12 was his son from his first marriage, and R. Meir Bar-Ilan13 was his son from his second marriage.14 The Netziv had several siblings, many of whom were part of the Torah world.15 R. Baruch Epstein16 was the Netziv's nephew, and R. Chaim Soloveitchik of Brisk married the Netziv's granddaughter.

- Teachers –

- Contemporaries – R. Yitchak Elchanan Spektor, R. Yosef Baer Soloveitchik

- Students – The Netziv influenced thousands of students at the Volozhin yeshivah, including many of the religious and intellectual leaders of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Works

- Biblical commentaries

- Ha'amek Davar17 – The major portion of a Torah commentary based largely on material originally presented in the Netziv's daily Parashat HaShavua shiur in the Volozhin Yeshivah. A separate section of the commentary, entitled Harchev Davar, presents more extensive discussions.

- Rinah Shel Torah18 – A two part work consisting of a commentary on Shir Hashirim (Metiv Shir) and an essay on the roots of anti-Semitism (Shear Yisrael).19

- Devar HaEimek20 – A collection of excerpts from the Netziv's writings related to verses in Neviim and Ketuvim.

- Rabbinics

- Talmudic novellae – Meromei Sadeh21

- Commentaries

- Responsa and letters

Torah Commentary

Characteristics

- Verse by verse / Topical –

- Genre –

- Structure –

- Language –

- Peshat and derash

- The commentary exhibits the Netziv's extensive knowledge of Hebrew grammar and syntax, and displays the Netziv's commitment to the method and content of Midrash Halakhah31 and to the teachings of the Oral Law in general.32

- The commentary is significantly influenced by the Netziv's Lithuanian Mitnagdic focus on the religious significance of Torah study.

- In his introduction to the commentary, Kidmat HaEimek,33 The Netziv sets forth a view of peshuto shel mikra based on the understanding that the Torah is generally meant to be interpreted more as poetry than as prose. Since poetry clearly intends for the reader to employ a subtle, less obvious kind of interpretation, readings that otherwise might be viewed as derash can actually be considered peshat.

Methods

- –

Themes

- –

Textual Issues

- Printings

- Ha'amek Davar was initially brought to press by the Netziv himself, and published in 1879-80. From that point until the end of his life, the Netziv recorded additional commentaries and notes (mostly written in the margins of his personal copy of Ha'amek Davar).

- In 1938, a second edition was published by R. Meir Berlin (Bar Ilan), which included some 1500 additions.34

- In 1999, a new edition of Ha'amek Davar was published that incorporated the additions into the body of the commentary, and included further comments not included in the 1938 edition, taken from a manuscript the Netziv had written near the end of his life in preparation for republishing the work.35

- From 2006-2011, a new annotated edition was produced by R. Mordechai Copperman.

- Textual layers –

Sources

Significant Influences

- Earlier Sources –

- Teachers –

- Foils –